The worker, weaver, traveler and dairymaid, Sigríður Anna Jónsdóttir, was born at Gerðarkot below the Vestur-Eyja Mountains on the 20th January 1901. Later, in the spring of that year her parents moved to Moldnúpur in the same region. She developed such strong ties with Moldnúpur that all her life she called herself after the place. It was there that she was raised, playing and working in the traditional countryside way, but also with a good share of culture, reading and conversation. In her youth Anna once accompanied her father on a sea-fishing trip off the southern coast and always fondly recollected this experience.

Who is Anna?

Anna attended school for eight weeks each winter from the age of ten to fourteen. Then she undertook an apprenticeship in weaving and ,though still in her youth, was soon beginning to weave for people. When the Laugarvatn Provincial School was founded Anna took the opportunity that it offered and went through some further schooling. She was in the school’s upper class during the winter of 1929-30. To finance her studies Anna took a loan of 400 króna, with her father and brother acting as guarantors. She called it her dowry.

However, that winter in Laugarvatn was not enough to satisfy her longing for an education. At the end of it Anna continued on to Reykjavík and began to study at a school that offered instruction without an attendance requirement. While doing this she also was working for a living, mainly by weaving. Later she applied for permission to spend a winter in school in order to prepare for the school matriculation exam, but this was denied her. Unfortunately she never became a college student, but instead pursued her own education. This continued all her life and took the form of reading, travelling and studying foreign languages.

Anna’s first published writings were newspaper articles. She appears to have first burst forth onto the literary field late in 1942, with a straightforward article in the Alþýðublaðið newspaper about church buildings in Reykjavík. The article led to a polemical exchange with the historian Sverrir Kristjánsson, undertaken by Anna with much zest. During the following years Anna initiated similar debates with other nationally famous figures. They centred on matters of politics and culture and Anna appeared to be a representative of the viewpoint of the general public. She was not to be browbeaten anywhere. She was convinced that her viewpoint and opinions had as much right to be heard as those of the “upper class gentlemen”, as she sometimes termed her opponents. She also wrote much on countryside issues, for example on the plight of farmers after the eruption of Mt. Hekla in 1947, and on the great loss suffered by her rural neighbours when their library was burnt to the ground. It was almost as if it were Anna herself that had been destroyed.

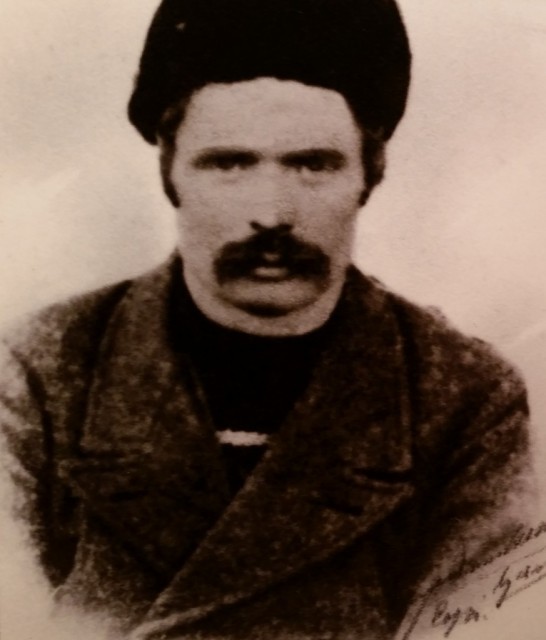

Anna's Father

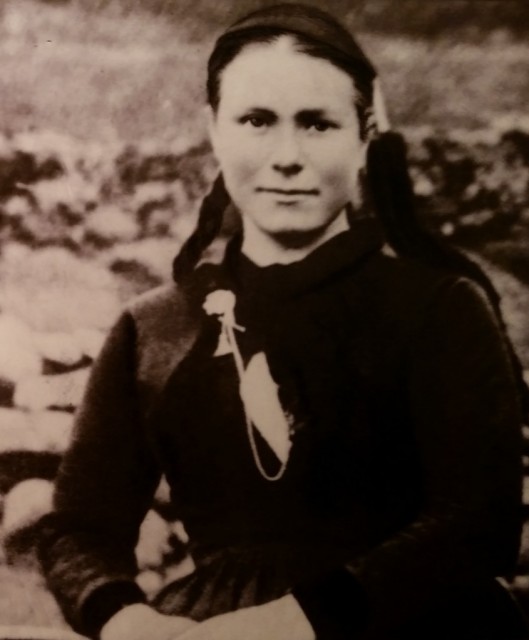

Anna's Mother

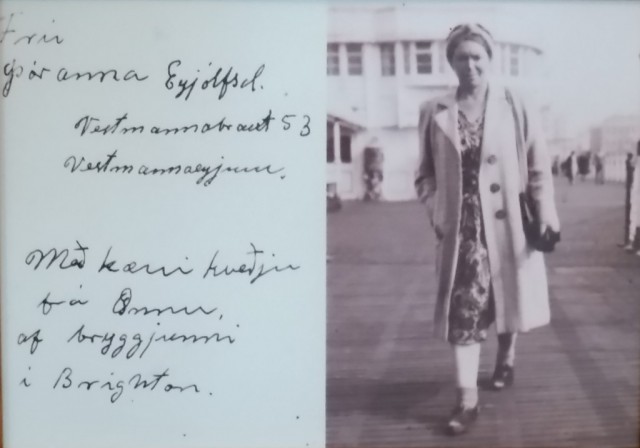

Around the middle of the century Anna mostly gave up writing newspaper articles. She was approaching fifty and had been seized by an urge to travel. In the spring of 1947 she boarded a ship intent on spending the whole summer in Denmark, even though at the time her only previous foreign travel had been one trip to England. The following year Anna went to England and continental Europe. In the summer of 1950 she went to Paris, and she travelled south to Italy in the summers of 1956 and 1959.

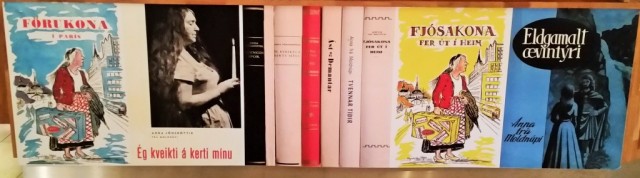

Anna wrote books about all these travels. A Dairymaid goes out into the World was published in 1950 and A Woman Traveller in Paris came out two years later. Others included Love and Diamonds in 1954 and I lit my Candle in 1961. The last journey Anna wrote about was her grand tour of America in the summer of 1964, which was narrated in the book Two Seasons (1970). In addition to these travel tales Anna also published the children’s story An Ancient Adventure (1957) and a book of memoirs about her father entitled Following in his Footsteps (1972).

Anna published all these books at her own expense and did most of the marketing herself. All her travelling was done on a shoestring, but with plenty of optimism and hardiness. Travelling about she followed her grandmother’s motto: “If God intends you to live then he’ll provide you with the means.”

Anna’s travel tales are lengthy and precise descriptions of whatever she beheld. They show how the world appears in the eyes of a traveler. She had a great interest in the culture of the countries she travelled around and was most diligent in visiting churches, museums and notable antiquities. She did everything to acquaint herself with the people of the world she came across. It helped that everywhere she went she could speak the native tongue. She was fluent in English and Danish and could get by in French, German and Italian.

Anna was a frugal traveler, which resulted in her getting into many amusing situations. All her life she needed to live as frugally as possible and her dealings with those who provided her with shelter are often amusing. It would be difficult to find a traveller who was so spartan in her diet. Coffee was the only thing she could never say no to, except on one occasion up in the Eiffel Tower where the price was too exhorbitant. Nevertheless she was never mean and when the circumstances arose she would give to the needy from her own few krónas. In spite of her tightly rationed resources Anna somehow always managed to get home before the money ran out, though a reader of her books often fears that she won’t make it.

Anna of Moldnúpur passed away in Reykjavík in 1979. Without doubt her life’s experience ranks among the richest of 20th century Icelanders.

Sigþrúður Gunnarsdóttir.